Sunflower

The first major U.S. campaign for women’s suffrage was in 1867 in Kansas. Suffragists used the sunflower, the Kansas state flower, as a symbol of their cause. Earlier, Elizabeth Cady Stanton had used the pen name, “Sunflower.” Roses, Yellow and Red

Suffragists and anti-suffragists used roses or rose pins to indicate their support for or against the Nineteenth Amendment. Suffragists work yellow roses, while anti-suffragists wore red roses.

Suffrage Colors

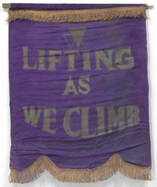

Yellow (Gold) Suffragists’ use of yellow flowers and yellow ribbons (or gold sunflowers) to represent the women’s rights movement and agitation for the vote began with their first campaign in 1867. White Suffrage women often wore white to indicate their purity and femininity. Since suffragists were often accused of being improper and unladylike, they wore white dresses in parades to make clear the pureness and wholesomeness of their cause. The National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs Purple and white were the colors of the National Association of Colored Women, which formed in 1896 to promote equality for Black women. Their motto was “Lifting as We Climb.” They used purple as a symbol of royalty, and white for purity, and sometimes added the traditional gold of the women’s suffrage movement.

British Women’s Social and Political Union In 1908, British suffragettes began using green, white, and violet (for give women the vote). Also, green stood for hope, white was a symbol of purity, and violet (or purple) represented royalty.

Suffrage Tea

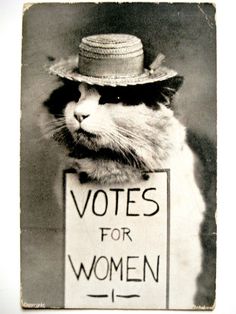

On July 9, 1848, five key members of the American women’s suffrage movement met for tea in Waterloo, New York. The participants in the tea party were Lucretia Mott, Martha Wright, Mary Ann McClintock, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and hostess Jane Hunt. As the women sat at the table set with Jane’s best teapot, cups, and saucers, they made plans for the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women’s rights conference in the Western world. Tea was again linked to the women’s movement by one of the legendary society hostesses, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont. In 1913, Alva had a Chinese tea house constructed on her back lawn. It seated over 100 guests for fundraising teas benefiting her new passion, woman suffrage. A year later, Mrs. Belmont hosted the “Conference of Great Women” at her Marble House mansion in Newport, where she and her daughter Consuelo, Duchess of Marlborough (Blenheim Palace), gave speeches to those assembled. The British potter Maddock & Sons produced sets of porcelain tableware bearing the “Votes for Women” theme as part of a luncheon service. The dishes were used again at a tea party held at the mansion in July of that year. Both events raised money to support the suffrage movement, and guests received teacups and saucers of the china as favors. Suffrage, suffragette, suffragist, suffragent

Many women were “suffering” and still are. In the 1800s and early 1900s, women suffered from oppressive or unjust treatment in homes, workplaces, churches, courts, banks, shops, schools, and colleges. Some even endured physical abuse and emotional torment. However, the word suffrage does not mean suffering. Suffrage means “the right to vote.” It originates from the Old French “sofrage” meaning plea and from the Latin “suffragium” meaning support, ballot, vote. Its first usage in English with the meaning “political right to vote” was in 1787 in the U.S. Constitution. Suffragettes refers to British women working for the vote. Initially, it was a derogatory term but the women adopted it and re-purposed it. Women suffrage workers in the U.S. did not adopt the term; they called themselves suffragists. Men who supported the woman suffrage movement were sometimes referred to as suffragents. Some women could vote in 1776

New Jersey’s first state constitution (1776) allowed women and blacks to vote if they met property requirements. Essentially only unmarried women and widows could vote because married women could not legally hold property in their own name. Suddenly, in 1807, New Jersey rescinded the “right” from women and other groups. Due to voter fraud (such as men dressing as women to cast a second ballot) and women gaining too much political sway, New Jersey adopted the policy of other states and restricted voting to “free, white, male” citizens. Suffrage was not suddenly “given” to women

The struggle for women to re-gain or obtain the “right” to vote lasted decades. It was not a generous, thoughtful gift delivered willingly. Thousands upon thousands of women and men battled for the cause. The Name Game In addition to working for national suffrage groups, women from New York State also created their own suffrage organizations at the state or regional level. By 1915, so many organizations had headquarters on or near Fifth Avenue in New York City that writer Marie Jenney Howe called it a “Suffrage Hive.” Mrs. Howe recalled a prominent male magazine reporter telephoning her for an explanation of suffrage groups in the city. “Would you mind telling me the name of the suffrage organization?" he asked. "Which one?" replied Mrs. Howe. "Oh, is there more than one? Well then, the most important.” Mrs. Howe explained that the National American was the oldest. "The National? Oh, yes. That is the one of which Inez Milholland is president?" "No, the National's president is Anna Shaw.” “Oh, yes. Miss Shaw, the actress.” “No, the actress is Mary Shaw,” snapped Mrs. Howe. “The National's president is Rev. Anna Shaw." "Oh, yes, I know now. Her headquarters are in Washington." "No, her headquarters are in New York." "Oh. I thought the New York headquarters belonged to Mrs. Belmont.” "Mrs. Belmont's association's headquarters are in New York, too." "Both?” responded the confused man. “Are there two?" At this question, Mrs. Howe’s patience gave way. "See here, young man," she shouted, "Do you think you know enough to write an article on suffrage?" "No, certainly not. That is why I called you on the telephone." Mrs. Howe gave him a list of several New York suffrage headquarters and hung up the receiver. After she recovered from the heated conversation, she felt a measly ounce of pity for the magazine man; perhaps he was not completely dim-witted. Upon reviewing her list of suffrage organizations, there did appear to be some basis for confusion. At 303 Fifth Avenue was the Empire State Campaign Committee of NAWSA, chaired by Mrs. Catt, who was also president of the Woman Suffrage Alliance. The same building housed the headquarters of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association, led by Gertrude Foster Brown. Other NYC headquarters included: Woman Suffrage Party at 48 East 34th Street, led by Mary Garrett Hay; Women’s Political Union at 25 West 45th Street, president Harriot Stanton Blatch; New York headquarters of the Congressional Union at 15 East 41st Street, headed by Alva Belmont; and, Men's League for Woman Suffrage at 11 Broadway, headed by banker James Lees Laidlaw. There was also the Equal Franchise Society, Political Equality Association, Collegiate League, and so many other groups and clubs. No wonder the young magazine reporter was so befuddled. How could anyone make sense of the jumble of names and addresses? “If you only knew the unnecessary letters we have to write,” said Mrs. Howe, “and the postage stamps we have to waste, just because the general public gets our headquarters mixed!” Several gentlemen had suggested that all suffragists join together in one organization. “It would be so much easier to remember,” asserted the men. But why should the women do so? To save a few stamps? To unburden men’s memories and protect them from exertion? Marie Jenney Howe believed the tremendous gain in activity and energy outweighed any losses to men’s understanding. The suffrage groups agreed on the overall goal: votes for women. On the surface, the organizations seemed to be facsimiles---all focused on woman suffrage---however, each group had its own innate attraction for a different group of women (and men). Whether it be geographic proximity, religion, race, philosophy, or occupation that brought the group together, the comradery generated enthusiastic participation. Suffragists encompassed a wide swath of society and employed a variety of strategies. Was there some duplication of effort? Sure. Confusion? Sure. Results? On November 6, 1917, New York State approved woman suffrage. |