|

Observers often underestimated the women’s efforts. These drill movements required hours of practice and entire books were written to provide assistance. Barnett’s Broom Brigade Tactics included the nomenclature of the broom and instructions for skirmishing, fan drills and silent drills (sans commands). Most important, it provided a “Manual of Arms” with instructions for each command and conformed as nearly as possible to the one practiced by the Army: Present arms! Reverse arms! Load! Aim! Sweep! Forward in line, charge!

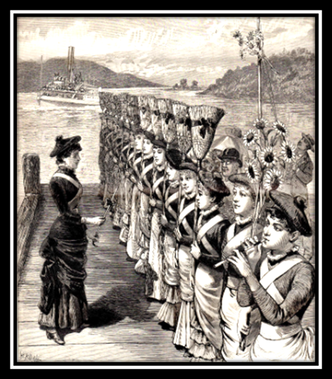

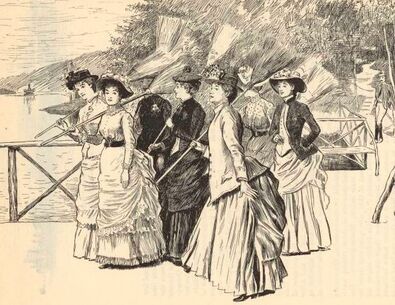

According to Barnett’s manual, the captain of the squad needed a good ear for time and a quick eye to detect any movement that was too fast or too slow. Her role also required self-control, “a sweet temper,” and a long feather-duster for commanding the soldiers. For performances, the women trimmed their brooms with a bow and monogram, such as B.B. for Broom Brigade, and strapped dustpans around their waist as ammunition-boxes. Some groups wore white bib-aprons with high-crowned, white muslin caps, but costumes varied. With time and practice, and a slew of stitches, all of these components came together. At the command “Order brooms!” the brushes whacked the floor in unison. Upon another command, the recruits whacked the dustpans with their right hand and then whacked the brush of the broom. After “Fire!” they sang out “Bang!” in a tone of terror. Then they marched by fours back and forth on the stage and were applauded for their precise evolutions. Finally the marchers were gaily mustered out of service and the church auctioned the brooms, dust pans, and caps of the broom brigade. These troops invaded northern New York towns such as Governeur, Gloversville, and Greenwich. In Ticonderoga, the school’s broom drill, under the direction of Captain Bertha Mead, went through a variety of movements “with the regularity of clockwork.” Young ladies of the Malone broom brigade performed on Thanksgiving Day at the Lawrence Opera House, and “the proficiency with which they went through the different evolutions would have done credit to the 27th.” North Country newspapers also told of drill performances at churches of various denominations. The ladies of Ilion presented their broom exercises at the Episcopal Fair. In Nicholville, there was a military broom drill and an eloquent scarf drill at the Baptist Church, while at the Presbyterian social in Cape Vincent, ladies performed the drills with brooms and then fancy fans. In Upper Jay, the Methodist Church included a broom drill as part of its Christmas entertainment. Even the Universalists in Watertown watched a broom brigade performance. Besides being featured at school and church functions, broom brigades appeared at social gatherings, such as a lawn party at the home of William Ross in Whallonsburg and a parade in Keeseville. Yet not everyone fancied the broom drill. One gentleman in Plattsburgh had no interest in seeing the event. According to an account in a local paper, he refused a free ticket, insisting that he had seen enough of that at home. When the women of Plattsburg performed, the paper wrote, “well done, very pretty and interesting.” It was expected that the young gentlemen of the town would all want to enlist in the broom brigade or at least buy a lady’s broom at the auction that followed. Brooms generally sold for 50 cents or $1 unless the bidding became competitive, when it might fetch $10 or more. The New York Herald hailed broom drills as “a new and excellent device” for fundraising. The ice-cream social and strawberry festival had their glory days, as had the spelling bee and oyster soup supper. None could compete with the broom drill in corralling coins into a money box. Some women joined brigades solely for fun or fundraising, others for female fellowship. For many, it was a matter of asserting a new social identity. Having been excluded from participating in most sports, women wanted the opportunity to exercise. At some colleges, women demanded the formation of broom brigades as an equal recreational activity to men’s military units. Likewise, grammar schools incorporated drills for boys and girls as the recognition for physical education programs grew more popular. As the drill craze swept across the country, so did bicycle riding. Both activities proved that women were not weak or frail or timid, and both generated reform in women’s clothing, health, and social condition. Susan B. Anthony credited the bicycle with doing “more for the emancipation of women than anything else in the world.” While broom brigades had a lesser impact, they did demonstrate that women’s capacity for precision and grace was greater “than half the crack military corps of the country.” Broom brigades’ popularity faded by the turn of the century. But while they lasted they exhibited, in public, woman’s physical prowess and helped redefine her “proper place” in the 1880s and 1890s. Some groups, such as the Sunflower Brigade, also illustrated the innovative tactic of delivering a political statement --- all while having a rollicking good time. A shorter version of this article first appeared in Adirondack Life, July/August 2019. |